READ CHAPTER ONE OF JEAN’s memoir HERE.

The Forms That Hold Us, chapter two.

The sun was low when I waved and watched my father drive away, retracing the tire tracks we’d made in the gravel. His dusty Oldsmobile shrank into the distance, then disappeared. The moment was poignant. I felt sad, but not because I wanted to be with him. I was happy to be here now – in this place of new possibilities – and relieved to be free from the vague feeling of absence I often experienced with him. Through teary eyes I watched what was familiar vanish, leaving a cloud of dust dissipating into air.

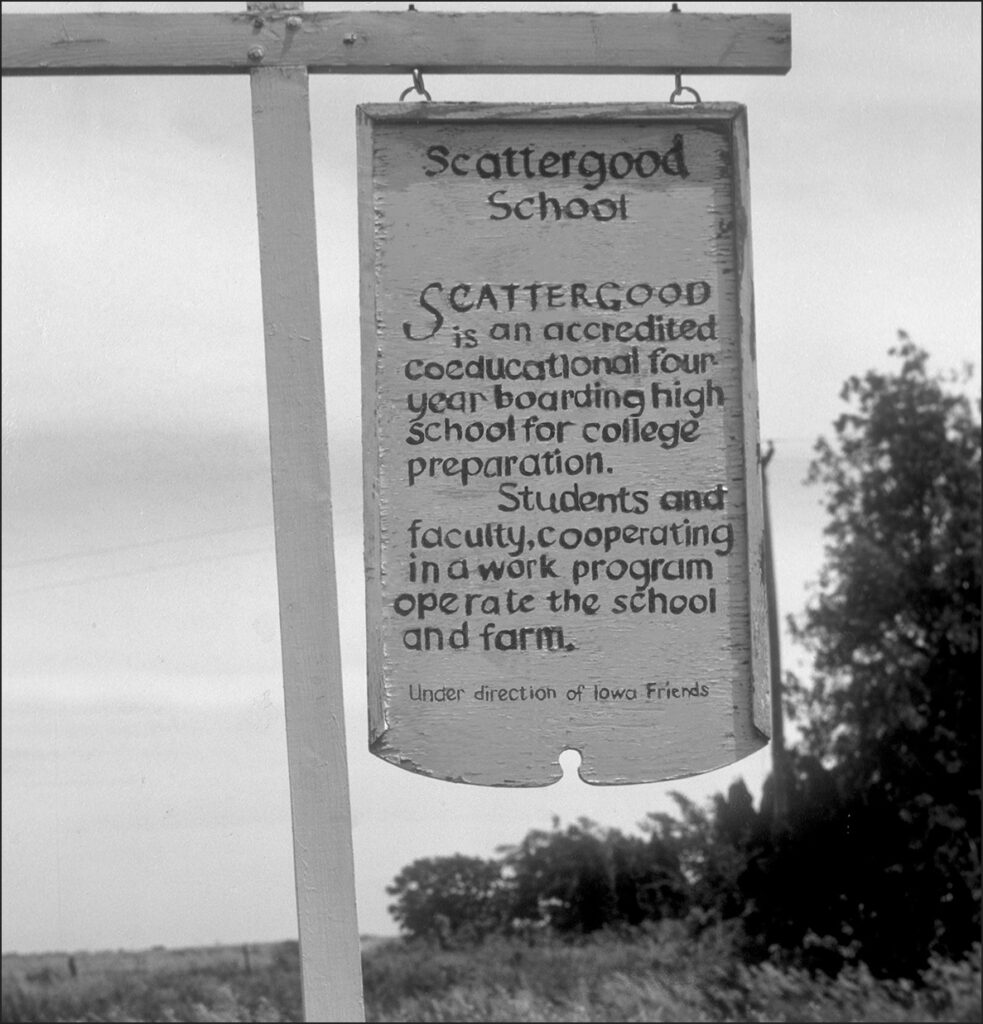

“Thank you for bringing me here,” I had said, stretching up awkwardly to hug his bony shoulders. I was truly grateful, and I wanted him to know, to feel appreciated. And despite our lack of words, I knew he too was happy for me to have this experience at Scattergood.

The best days of his life had been during the 1930s when, along with his first wife and family, he had directed Ashland Folk School in rural Michigan. Ashland was based on the Danish Folkehøjskole movement. The “schools for life” focused on community adult education that reached beyond book learning. Here they shared life skills, prepared people to be informed participants in democracy, and celebrated diverse cultures through group folk singing, dancing, games, and crafts. Our family photo archives included a picture of my father and mother folk dancing there in 1932, when she’d attended as a young student from a nearby college. She was smiling at him, wearing a long, full, Scandinavian-looking skirt with bright bands of color, that she’d made especially for dancing. Each time my father spoke about the Ashland days, his tone of voice changed, and I often heard the phrase “…the fine art of living human life…” In my young mind, the words and place fused together, leaving a strong positive impression, but no clear meaning.

I imagined now that Scattergood’s rural community setting, cooperative work program, and commitment to educating the whole person must have seemed to him an echo of those days at Ashland.

“Grahaaamly!” exclaimed Sarah when my sister Laurie appeared, using the nickname she’d acquired here during the past three years.

They’d both arrived with hugs and loud whooping that reverberated through the dorm hallway. Each time a student returned, voices raised to a crescendo, creating a kind of modulated soundtrack for the day. Laurie looked tan and happy with her longish brown hair and dark eyes. Unlike me, there wasn’t a freckle to be found on her clear skin. She was part of a close-knit senior class, eager to reconnect and catch up after being apart for the summer. Our freshman class was brand new, with fourteen students including Sarah and me – seven girls, seven boys – all of us just beginning to get acquainted.

Sarah’s room was down the hall from mine, and both of her roommates were seniors – one from Germany, the other from Indiana. They seemed sophisticated, worldly, and hip to all the inside secrets of life. I thought she was lucky to be with them. I settled into my room with Bonnie, a tall red-headed junior from Texas with remarkably upright posture and pointy breasts, and Rosy, a sweet, sometimes timid senior girl from Iowa.

“We three are an unlikely combination,” I thought the moment we first met, but over time, in such close proximity, we grew to understand and like each other. We all had our quirks. I became fascinated with the elaborate protocol Bonnie used for treating her adolescent acne. This involved standing for extended periods in front of the mirror, using swabs with alcohol, a sharp needle stuck into a cork, and various beige creams. During the process, she was diligent and good-humored. Rosy and I would exchange glances. We were much more casual about our self-care.

On that first day, all of us were immediately swept into the scheduled community activity of the school year. It propelled us along unceasingly, like the flow of traffic that roared by day and night on Interstate 80. Like the highway, the schedule provided little respite. You could stand on the nearby overpass and watch the cars and trucks come and go for miles – east and west – without pause. Laurie’s stories about students ice skating on the unfinished highway just a few years earlier seemed unimaginable.

Our time was fully scheduled except for Monday afternoon, a couple of hours on Sunday afternoon, and a scant half-hour “social hour” before dinner each night.

Classes were held all day Tuesday through Saturday. Our “Saturday” was on Monday, scheduled so that our free afternoon didn’t synch with the townies’ day off in West Branch. We were told this schedule made it easier for students to get doctor appointments and haircuts, but we knew it was to prevent us from playing pool with the townies in that dark, smoky backroom of the Dew Drop Inn on Main Street.

The girls and boys could go to West Branch on alternate Monday afternoons. On girls’ day, we hopped on our bikes, after first pulling up jeans under our required skirts. This hid our underwear when gusts of wind inevitably blew the skirts up into our faces while we pedaled along. The two-mile trip on the gravel could be rough riding, and I still have Iowa pebbles ground into my knee from falls on that road. Once in town, we had the excitement of exploring one café, one grocery store, and one creamery. The freshly-made ice cream at the creamery was the best and used local milk.

Every night after dinner we had study hall, followed by Collection – except on Saturday, which was our social night. Social events ranged from watching a movie or play, or having dinner at faculty homes, to playing an all-school game or folk dancing on the campus Circle. Collection meant that all the students and staff gathered in the social room of the Main Building, sitting on chairs or on the floor, to discuss community issues, read a story, sing, or listen to a guest speaker. The range of topics was broad, but we were always collected together. Leanore was the choreographer, and this was her time to check in with us.

On Sunday morning we slept an extra hour, to accommodate the weekly faculty meeting that Leanore held in her office from 6 to 8 am – a time probably dreaded by the faculty. As a special treat for breakfast, we ate coffee cake and corn flakes instead of the usual hot cereal or scones. After cleanup there was Pre-Meeting, when we were presented with thought-provoking topics before gathering for silent worship in the Quaker Meeting House.

I liked being in the old-fashioned Meeting House – boys on one side and girls on the other, seated in rows looking towards the “facing benches” at the front of the room. These were originally intended for the esteemed elders, who wore simple gray clothes and “eldered” people to uphold the Meeting values. Now only a few faculty members sat there, and all of us wore an array of somewhat formal clothes, but nothing very dressy. The space was silent and plain – no pretense, no pictures, no distractions, no pressure. I was accustomed to the hour-long silence, but I think even the non-Quaker kids grew to appreciate it.

I liked being in the old-fashioned Meeting House – boys on one side and girls on the other, seated in rows looking towards the “facing benches” at the front of the room. These were originally intended for the esteemed elders, who wore simple gray clothes and “eldered” people to uphold the Meeting values. Now only a few faculty members sat there, and all of us wore an array of somewhat formal clothes, but nothing very dressy. The space was silent and plain – no pretense, no pictures, no distractions, no pressure. I was accustomed to the hour-long silence, but I think even the non-Quaker kids grew to appreciate it.

Of course, we heard the endless drone of engines whizz by on the interstate, reminding us of the outside world. But even that transformed into a soothing white noise, like people now use to help them relax and fall asleep. Sometimes a student, and more commonly an adult, stood to share a message. This felt different and somehow more intimate than my experience of the Madison Quaker Meeting. Here we all lived closely together, and more of us were peers, making any message feel relevant, and often very moving. It took nerve to stand up and speak, breaking the rich and potent silence. We were to speak only when following an “inner leading,” and that was difficult to discern.

After Meeting for Worship on Sunday, we had lunch, and then a mandatory two-hour “Quiet Hour” in our dormitories. We were confined to our rooms and could not make loud noises, so this was a good time to read or rest, or to pass notes, room-to-room, across the open top of the walls. It was also the time we brought out our illicit electric coils to make steaming cups of coffee, and share care packages of snacks from home, or scones that someone had smuggled up from the kitchen. In good weather we cranked open our windows, inviting in the fresh air.

One Sunday I was caught mid-action, perfecting a new skill. I had prepared by bringing in the communal iron from the girls’ bathroom. There was a knock on the door.

“Who is it?” asked Bonnie and Rosy simultaneously, sounding as innocent as possible.

I was scrambling. Using cheese and Scattergood homemade bread that I’d buttered, I had assembled a sandwich, then wrapped it completely with aluminum foil. This silver package lay balanced and sizzling on top of the hot iron I held face up. It was just beginning to transform into a delicious toasted cheese sandwich.

The door opened. It was Charisma Riggle, the girls’ dorm sponsor who also taught us math – a wide woman with heavy footsteps. The toasty smell that I so wanted to taste had been my downfall. There was nowhere to hide. She confiscated the iron and led me down to her room at the end of the hall, where she reprimanded me. “You know better than that!”

Consequently, this was one art form I never perfected.

Our girls’ pranks were pretty harmless. Sometimes we coordinated a door slam – kind of like “the wave” that people began to do at football games – doors slamming one at a time, up and down the hall. The boys were more active and aggressive in their Quiet Hour exploits. I heard stories of a boy who rigged up a container of water that fell on the dorm sponsor when he opened the door, and someone who used a hand-cranked generator to electrify a wire under a bed sheet to shock his roommate.

Sometimes the boys plotted and enacted elaborate schemes. One involved our German teacher.

“Let’s put Karen’s cool little MG inside the Main Building! When my brother was here, they pulled off something similar. And that snazzy car would look great inside… We’d be careful not to damage it.”

“But how?”

“We can do it on Sunday morning when all the faculty are in Leanore’s office. It’s a stick shift, a two-seater and can’t be that heavy. We’ll roll it down the driveway to the kitchen door, then push it across the grass around to the dining room double doors. Then we’ll just have to lift the front to get the wheels up onto floor level. It’s only one step.”

“Uff da! We’ll need a lot of guys to lift and push.”

“Just make sure breakfast prep crew is in on it. And we better remember how to say ‘sorry’ in German!”

The following Sunday morning, we walked down to the dining room to find a sporty canvas-topped MG parked amongst the tables. Karen’s face looked a bit flushed, but she acted cool, like nothing had happened. Breakfast continued, with coffee cake suppressing many outbursts of laughter. We knew the consequences would come later.

After Quiet Hour there was free time, and we girls could choose to play sports with the boys – soccer on the field in good weather or boys-rules basketball in the drafty wooden gym when we had to be inside. Boys-rules meant we could keep bouncing the ball down the court instead of jerking to a stop after only three dribbles. That felt like freedom.

At 4pm sharp, Sarah stuck her head through my dorm room door. Bonnie and Rosy were used to this, but regardless, they were napping.

“Let’s go!” she said, already dressed in jeans and sneakers. She went out to play every Sunday, and I often accompanied her. Bending over, I finished putting on my shoes and headed out the door.

The soccer field was between the interstate and the farrowing barn, which was renamed the Pig Palace. We liked to be with the boys, and it was a challenge to learn a game that girls did not play in the early 1960s. Even boys in public schools didn’t play soccer. Our girls recreational sport was field hockey, which we played with well-used wooden hockey sticks, wrapped in layers of tape. We played until the snow fell, and even then, continued by painting the ball orange to make it visible in a field of white.

I loved watching the finesse of the boys’ foot-dribbling down the field and bouncing the ball off their foreheads, with the Iowa landscape as the background – cars zooming by on one side and sows grunting along the other. Beto, a small, compact-framed boy from Mexico City who’d grown up playing soccer, was particularly acrobatic in his leaps and head bumps. We considered him our Olympian and I was mesmerized. He looked like a dancer to me, and I’d never seen a head used as a tool in that way.

We played past exhaustion, running up and down the field, until we heard the dinner bell, or saw our shadows lengthen towards the Main Building. Then, out of breath and feeling our blood pulse through every cell, we headed towards the dorms.

The compulsory Scattergood schedule was rigid and seemingly unsuited for teenagers, but the camaraderie we developed made it tolerable. We were in this together. We bonded through our side-by-side activities – day and night – in the dorm, in class, in work, in creative resistance-actions. There was that zing and electrical charge we felt being close to our adolescent peers. For me, as a freshman girl, the junior and senior boys seemed especially exciting, and it was easier for me to get to know them while we did activities and quotidian projects together. Table-seating arrangements changed regularly, and even roommates changed halfway through the year, so we interacted with everyone. This was intentional. Cliques were discouraged.

All students were expected to participate in the chores required to maintain the school. Monday morning until noon, we had work crews, and two 45-minute periods daily, morning and afternoon, depending on what our task was. Crews were assigned on a three-week rotation, and we had no idea what our next chores would be.

“Hey! What did you get this time?”

We’d wait for the new schedule to be taped onto the pole in the center of the lobby. It might be washing dishes, pots and pans, meal prep, bread baking, laundry, farm chores, office work, cleaning, maintenance, or grounds work. All crews were gender-neutral; the boys did laundry too and the girls milked the cows.

I was lucky to get farm chore crew before the cold winter arrived, as did both my roommates, which kept the sleep disruption in the dorm confined to one room. For three weeks we got up at 5:30 each morning.

BRRRRRINNNNNG! The alarm! Groan!

The three of us climbed from our beds, slightly comatose. The beds were narrow and quite hard, and since the heat was categorically not turned on until after Thanksgiving, during the weekend of “Scattergood Day”, the room was often very cold. I’d heard the boys complain about ice on the plywood boards beneath their mattresses, and I wondered whether this rule was determined by some conservative principle, or simply the lean budget.

Half asleep, we pulled on our jeans and sweatshirts, and walked down the hallway and stairs, past Leanore’s office, and down another flight of stairs toward the kitchen. The breakfast prep crew was already making scones and hot cereal, and we greeted them as we reached the chore crew closet near the outside door. There we pulled on our knee-high rubber boots and jackets, grabbed two ten-gallon milk cans, and headed out into the dark morning.

The walk to the school farm was about a half-mile across the fields towards the west. We crossed the Circle, passed the boys’ dorm, and before we reached the soccer field, cut through the apple orchard. Sometimes I plucked an illicit Golden Delicious from an unpicked tree. I liked them best fresh, rather than waiting until they became shriveled and wrinkly after months of storage in the “Apple Room” off the dining room in the Main Building. Near the Pig Palace, we climbed over a wire fence before heading across the open field. We took turns carrying the empty milk cans. In the fall at dawn, chirping grasshoppers were awake and active. Sometimes they jumped into our boots as we trudged along, hoping to escape their death by frost.

“EEEEEUuuuuu!” squealed Rosy, wrinkling up her nose.

She set down the milk can and sat on it, quickly pulling off her boot and shaking it upside down. We could barely see the fat grasshopper that fell, then leaped into the thick stubble of the field.

“Gross! That was a big one!”

Nearing the barn, the light of dawn began to glow behind us. Alan, the farm manager, a Scattergood graduate, already had the cows in the milking parlor when we arrived. He had come over earlier from the farmhouse across the driveway where he lived with his wife. The cows munched on fresh, sweet-smelling hay, with their heads latched into metal stanchions. Four of them stood in a row – black and white Holsteins. They seemed vaguely familiar, being emblematic of my home state, Wisconsin, but I hadn’t known one personally before. Now I was up-close. They were big, and seemed to chew constantly, their thick lips curling and slobbering around the hay.

Our job was to wash down their udders with soapy water and dip them in iodine to help prevent contamination and mastitis. The water felt cold, but the large-bodied cows radiated heat as we pressed close to them. We crouched down and squeezed their teats by hand to make sure the milk was ready to go. The udders were taut with weight. I wrapped my index finger and thumb around the top of a teat in the way I’d been instructed, squeezed, and followed with pressure from my remaining three fingers. Milk squirted on the ground. We kept a wary eye on their hooves, watching for an imminent kick in response to a fly or an irritating action we had unknowingly inflicted on one of them. A kick hurt, and we were intent on avoiding the pain. We also watched their swishing tails, hoping to notice when one would rise, allowing a gush of urine or manure to splash down into the gutter. I decided then that there were better words to describe a “cow pie.”

One at a time, the farm manager attached the teats of each cow’s udder to a milking machine, and the rhythm of the vacuum pump sucking filled the room. Whoosh Click… Whoosh Click… Whoosh Click… It was a comforting sound, and the smells were a pungent combination of hay, mammary glands, manure, and iodine. We were quiet so as not to upset the cows, but Alan spoke to them by name: “Move over Francey!” “Atta girl, Martha.” I liked to hear his bass-tone “MmmmBosssss” echo through the building as he urged the cows out of the stanchions and released them into the pasture, making room for the next ones.

Alan was excited about plans to build a new milking parlor. His eyes lit up.

“We’ll build it so that we are standing lower than the cows. That way we won’t have to crouch down to milk them. I have the design. We’ll start building forms and pouring cement this spring and be done by summer. Whadda ya think? Will you gals volunteer to help?”

Later that year I did volunteer, and I enjoyed shoveling the cement and gravel into the rotating cement mixer, already filled with sloshing water. Between shovelfuls we joked and flirted with the boys. When the mixture was ready, the older boys dumped the lumpy mass into a wheelbarrow and rolled it into the barn where it miraculously solidified into a durable, useful structure. This was my first of many experiences with cement.

Our morning chores were complete when the cows’ udders were empty, and all the milk was collected into the cooler tank. Alan filled the empty cans we’d brought over with cold milk for the next day’s school consumption. The cans were now too heavy for us to carry, so he lifted them into the back of the pickup truck. The three of us climbed in next and found a place to sit in the open truck bed, where we could steady the cold cans. Alan started the engine and drove us into the morning sun, back to the school for breakfast at 7:00 am. We huddled together, unable to hear each other while the windy wake whipped hair across our eyes and mouths.

“I’m ready for some scones!” I shouted into the wind.

These kinesthetic farm experiences were perfect for me. I loved animals and experiential learning, and my mother had already fully prepared me to be a good worker. One of her favorite mantras was, “A job worth doing is a job well done.” She taught us how to paint wood correctly, how to pull a dandelion with its taproot intact, how to cut our toenails straight across, how to form hospital corners when making a bed. I had sometimes objected to a required task but always liked learning and the physical process of doing things.

From time to time, special opportunities arose outside the regular required Scattergood schedule. One Monday afternoon I volunteered to go sweet potato gleaning at a farm near the Mississippi River. About five of us, accompanied by a faculty member, drove towards Conesville, across the Cedar River and through more rolling fields, and stopped just short of the Mississippi. The farmer was waiting in the cab of his dusty pickup, parked at the side of the road. He smiled at us under the shadow of his yellow and green, brimmed, DeKalb seed cap.

“Thanks for coming. This here is the field. It’s been harvested. You can take whatever you find – just dig carefully. Sweet potatoes bruise easily.”

We stepped onto the clumped, uneven terrain, carrying bushel baskets. The harvesting blade had left the black earth heaped in disarray, with an occasional orange potato poking above the surface. Each of us took a row and dug through the soil, looking for tubers that the mechanized picker had missed. Some had been too small, and others were cut in the process, but whatever we found we put into our baskets.

First, we used our hands, then took off our shoes – something never allowed outside the dorms. It was a sensual thrill to press our naked feet into the dark soil. This was much more exciting than adding more sweet potatoes to our diet. We were giddy, marching around the field discovering potatoes, knowing we had hit the jackpot, just being able to leave the campus for the afternoon.

One November Leanore salvaged 900 pounds of grapes from a train wreck near Cedar Rapids. She was good at getting free food. Classes paused while we processed grapes into juice and jam and desserts. Grapes were everywhere – purple water, purple fingers, purple tongues!

Several daring boys smuggled juice into their closets and assembled crude wine-making operations. When some of their containers exploded in a smelly mess, one of them “borrowed” rubber hoses and corks with glass tubes from the science lab to use as fermentation airlocks. For weeks the half-gallon jugs gurgled. When the dorm sponsor came by for a room check, they played the guitar loudly or bounced a ball on the floor, to disguise the sound. One of them told me later that his first experience being tipsy was in the field between the farm and the dorm, where he and his friend lay on their backs laughing, with a canteen of yeasty, fermented grape juice at their side.

Every two years, on a work Monday, the older hens in the school flock were harvested. We had chicken-killing crews, chicken-plucking crews, and chicken-cleaning crews. The entire day became an extended science lesson.

“Weird! How does that chicken run with its head cut off?”

“Why are we pulling soft-shelled eggs and double-yolkers from inside these dead chickens? They feel so squishy and leathery!”

“Look! This one doesn’t even have a soft shell!”

The kitchen reeked during the cleaning process. I wrapped a scarf around my nose and walked by quickly, wondering whether I would ever want to eat chicken again. For sure I didn’t want to be a chicken cleaner, pulling organs from the dead bodies. I escaped out the back door and walked towards the henhouse where the killing was happening. Sarah was designated a plucker, and I was then tasked with tying the decapitated chickens by their feet from the clotheslines, to drain out their blood. This would keep them from running headless and headlong into the bushes. It wasn’t easy. We were set up outside near a vat of scalding water. The process was this: chop off head, drain blood, scald to loosen the feathers, and pluck. Then off to the kitchen to clean.

“Aaaaaaaaaack!”

Sarah had a distinct squawk that often morphed into maniacal laughter. “There’s a mass of maggots surging up at me!” She backed off from the garbage pit where she was depositing feathers.

We persevered until it was time to gather more chickens from the henhouse. Pulling off our gloves, we retreated behind a nearby shed that backed up to the interstate, both of us emoting forcefully about the gross tasks we’d been doing, and relieved to have a break.

“Let’s try to smoke!” said Sarah mischievously, pulling out a small pack of cigarillos she had somehow purchased at a tiny farm store she’d walked to several miles down the road. Neither of us had ever smoked, and we struggled to get the brown papery cylinder lit, sucking on one end while holding match after match to the other. The tobacco odor was strange and unpleasant, but better than the chicken smell in the kitchen. Finally, the flame took hold, and we alternated puffing on it, mostly pretending. With each attempt we stifled a coughing fit or a contagious burst of laughter.

Hearing something, we looked up – nervous about our illegal activity and the telltale smoke we hoped was blowing towards the highway.

Something had moved at the corner of the shed… and was coming closer…

“Eeek!” A severed yellow chicken foot moved towards us with its sharp claws opening and closing. We grabbed each other and dropped our incriminating cigarillo. Behind the threatening talons appeared one of our favorite senior boys, pulling the tendon so the chicken foot flexed as if it were still alive.

“Caught-cha!” he said. Then he doubled over with laughter – and we did too.

He never gave away our secret, but he never once let us forget it, sometimes grinning or winking at us as we passed in the hallway near study hall.

Neither Sarah nor I ever became smokers.

The highlight our sophomore year was raising a litter of pigs. Each of us, as part of biology class, was assigned a sow, and was responsible for raising her litter from farrowing to market. This meant the whole shebang – being with her during the birth, cleaning the piglets, keeping them safe from being crushed by her large body, clipping their teeth, notching their ears, giving them shots, and making sure they thrived. Twice a day that fall we trudged out to the Pig Palace to feed and water our sows, clean the pens, and watch for signs of imminent birth.

The highlight our sophomore year was raising a litter of pigs. Each of us, as part of biology class, was assigned a sow, and was responsible for raising her litter from farrowing to market. This meant the whole shebang – being with her during the birth, cleaning the piglets, keeping them safe from being crushed by her large body, clipping their teeth, notching their ears, giving them shots, and making sure they thrived. Twice a day that fall we trudged out to the Pig Palace to feed and water our sows, clean the pens, and watch for signs of imminent birth.

For the Quaker farm boys this wasn’t new. They were experienced. They could sit in biology class and identify what kind of tractor was passing on the driveway, just by the sound of its engine.

“That’s a John Deere.”

“Naww, definitely an Allis Chalmers.”

Their experience didn’t prevent them from getting squeamish the day we had to castrate our little male piglets. With bravado, they made a few jokes about Rocky Mountain oysters, but we could see a pallor on their faces, while one person held the pig tightly, and the other made two slits with the knife and popped out the testicles.

By serendipity, Sarah’s sow and mine looked like they might farrow on the same night. Our biology teacher had a VW bus, which she drove out onto the edge of the soccer field near the Pig Palace. Sarah and I were allowed to sleep in it that night so we could easily check on our sows’ progress. We got up every couple of hours, lighting our way into the farrowing barn with flashlights, though we probably could have simply followed our noses. Each sow was in a circular fenced pen, raised high enough for small piglets to escape from their mother, whose maternal instinct did not include looking carefully before flopping down. Our sows grunted and looked up into the light with squinty eyes, but no piglets were born that night.

At dawn, we woke to familiar voices outside the bus. “Are you awake? Jeanie? Sarah?”

There were our boyfriends, Ron and Alan. By now, we each had our first budding romance, and occasionally as couples we walked hand-in-hand around the Circle on Saturday nights or sat pressed close together under the weeping willow tree before dinner. Ron and Alan happened to be roommates, and they had sneaked out early from the boys’ dorm to see us. We invited them into the VW bus for an innocent, but out of the ordinary rendezvous. There was hardly room for them to come inside, so we stuck our heads through the sunroof and surveyed the landscape blanketed by the vast morning sky. The fresh air smelled like freedom. We were still shy and tentative in our intimacy. My first kiss with Ron came later in the photo darkroom, where I was flooded simultaneously with the new sensation of mouth-to-mouth kissing and the unfamiliar tingly flavor of Maclean’s toothpaste.

There were our boyfriends, Ron and Alan. By now, we each had our first budding romance, and occasionally as couples we walked hand-in-hand around the Circle on Saturday nights or sat pressed close together under the weeping willow tree before dinner. Ron and Alan happened to be roommates, and they had sneaked out early from the boys’ dorm to see us. We invited them into the VW bus for an innocent, but out of the ordinary rendezvous. There was hardly room for them to come inside, so we stuck our heads through the sunroof and surveyed the landscape blanketed by the vast morning sky. The fresh air smelled like freedom. We were still shy and tentative in our intimacy. My first kiss with Ron came later in the photo darkroom, where I was flooded simultaneously with the new sensation of mouth-to-mouth kissing and the unfamiliar tingly flavor of Maclean’s toothpaste.

That afternoon my sow farrowed. She was a gilt, which meant this was her first litter. I’d named her Ilithyia, after the Greek goddess of childbirth since no gods were specified for farrowing. I sat close by as she lay on her side in the straw, remarkably quiet, I thought. She made birth look so easy. The infrared heat lamps glowed in expectation, and I had a stack of dry rags, a clipper, and a bottle of iodine at my side.

She was a Hampshire hog with upright ears, black in color, with a white belt circling her body and front legs. Two rows of six nipples lined up horizontally between her front and back legs, and her solid body mass moved up and down slightly with each breath.

I watched her intently. “Come on, Ilithyia!”

Her tail twitched, and suddenly, after the hours of waiting, a perfect replica of her came squirting out, head first. Like a miraculous living torpedo, the piglet was wet and slippery from the lubricated birth sac, its umbilical cord still attached and intact. I tentatively picked it up and, as instructed, wiped the goo from its nose and eyes.

“You look like a little old man,” I said, holding him in front of my face and staring into his slanty eyes, outlined with surprisingly long lashes. He squealed, and when I set him down, he wiggled forward, instinctively knowing to search for the nipples, as if drawn by a magnet or a force of nature.

Several sophomore classmates gathered around to watch. Sarah was off with her own sow. During the next two hours, without fanfare, more squirted out – sometimes feet first, some males, some females, until there was a squirming black and white mass of eleven piglets sucking instinctively under the heat lamp. Several had stretched and broken their own umbilical cord in their enthusiasm to reach a nipple. Eleven was a perfect number, I thought, with one nipple to spare. Here was my new extended family.

When the afterbirth came out in a messy blob, that was the finale. I knew she was done. With difficulty, I picked up each squirming piglet, clipped its cord to a half inch, and put some iodine on the cut. Thus began the process of husbandry: clip teeth and notch ears within seven days, give iron shots, castrate the boys, wean from the mom, and then eventually send them on to the feeding floor.

That entire year we tried unsuccessfully to rid ourselves of the swine smell that clung to our clothes and hair and skin, despite all our best efforts. We showered and scrubbed, but it was the indelible mark of a sophomore. The other students were mostly tolerant, knowing they were only a year or two from being in our shoes. But they always steered clear of the designated closet in the dorms where the pig clothes were stored.

I never grew to like the smell of hogs, but ever since then, I have fiercely defended their intelligence and I display a motherly response to the squealing antics of little piglets.

This is not the only legacy I have carried with me from Scattergood.

Copyright © 2023 by Jean Graham

Copyright © 2023 by Jean Graham

Photos courtesy of Jean Graham

Jean Graham

The Forms That Hold Us

Jean Graham is a native Midwesterner with roots in the deep Iowa soil. She attended farm-based Scattergood School in rural West Branch, which sparked her love for making forms out of clay and inspired her life-long interest in ways that art can integrate with, impact, and create community. Jean recently completed a still-to-be-published memoir, The Forms That Hold Us, that traces her trajectory through the arts and her diverse experiences of culture and the land – from the Midwest to the subtropics and West Africa.