Chapter One: The Garter Stitch Dishcloth

Emerson, Nebraska, 1952

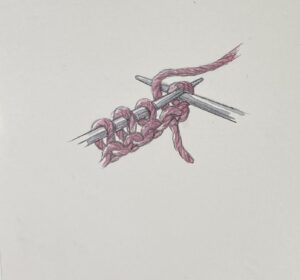

Knitting became part of me when Grandmother placed two shiny blue aluminum knitting needles and a skein of pink worsted wool yarn into my seven-year-old hands. She had already cast stitches onto one needle to start me off. She placed one knitting needle with cast-on stitches in my left hand, the empty needle in my right, and the skein of wool to my left side. Quite the balancing act for a small girl.

Grandmother talked me through each stitch. “Slip this right needle into the first stitch I cast on the left needle,” she told me as I struggled to grasp those notoriously slippery aluminum needles. “Now, wrap your wool around the tip of the needle, pick up a loop, and pull it through. Slip that loop onto your empty needle, the needle in your right hand.”

I had begun to hold my breath.

Each stitch felt an accomplishment, an acrobatic feat for a small child. I had short fingers for my age even then. Grandmother watched me knit a row of new loops. At the end of the row, she removed the knitting needles from my hands.

“Now, the right needle has the stitches, so you trade the right with the left needle. And remember the proper way to hold them.”

I began a second row, intrigued with the process.

“Keep knitting until you make a square, and you will have a dishcloth,” she said.

Grandmother was a superb and prolific knitter, and she was an immigrant, a Dane. Not unkind, but a Viking in strength and temperament. Her title was Grandmother. Grandma, Granny, Nana would have stuck in my throat. A sturdy woman with delicate features, dignified and tidy, always, from her skillfully permed white hair to well-tailored clothing and appropriately low heels. An American knitter of means, she bought yarn and patterns at upscale department stores in Omaha, where she made her home in her later years. She knit dresses and suits, afghans and bedspreads, baby blankets and bootees, sweaters, hats, socks, toddler snowsuits, whatever captured her interest in practical but up-to-date magazines.

Grandmother was a superb and prolific knitter, and she was an immigrant, a Dane. Not unkind, but a Viking in strength and temperament. Her title was Grandmother. Grandma, Granny, Nana would have stuck in my throat. A sturdy woman with delicate features, dignified and tidy, always, from her skillfully permed white hair to well-tailored clothing and appropriately low heels. An American knitter of means, she bought yarn and patterns at upscale department stores in Omaha, where she made her home in her later years. She knit dresses and suits, afghans and bedspreads, baby blankets and bootees, sweaters, hats, socks, toddler snowsuits, whatever captured her interest in practical but up-to-date magazines.

Her hands knew nothing of idleness. I remember her either knitting or twiddling her thumbs during occasional visits to our comfy bungalow in Emerson. Grandmother had lived 74 years by then, and I was her youngest, her last grandchild. I was also her eager student. Quiet and solitary by nature and circumstance, I had a natural love for making things with my hands. Perhaps she felt concerned that a granddaughter of hers had reached the age of seven and not yet learned to knit. Or perhaps she thought knitting gave us something to do together.

Grandmother liked to talk about knitting, as knitters do, her mind relaxed and wandering, while she watched me grapple with my rows of garter stitch loops.

“Some days when things haven’t gone quite right,” she said. “Knitting puts things back in order. I knit awhile before I go to bed and then I can sleep.”

Odd the way her exact words, a snippet of memory, have carried down the decades. Grandmother had many days during her lifetime when things had not gone quite right. A bride at nineteen, she once confided she was not quite sure where babies came from when she married. She would give birth to seven children and tend a bedridden husband through years of terminal illness until his death in 1937.

Grandmother knit continental style, as taught in Danish schools, with yarn held in her left hand, loops worked from the left needle and slid onto the right. It has been said that some American knitters rejected continental style during the world wars as too German, unpatriotic, and they switched to the more patriotic English style, or “throwing” with yarn held in the right hand and thrown over the left needle. Grandmother knit continental all her life. During World War I, her two oldest sons served, one a machine-gunner who returned home from action in France and a second who died during the war. I heard no one question her patriotism.

Grandmother lived most of her married life in Oakland, Nebraska, then in Emerson before her late-in-life move to Omaha. On her own in a roomy Queen Anne house in Emerson after her husband was gone and children off to live their lives, some days she walked up the hill to Rose Hill Cemetery, a peaceful place that overlooked the village and surrounding farm fields. She carried her knitting, perhaps in the same knitting bag that had held her wartime knitting during World War I—The Knitting War—when a large knitting bag was a badge of patriotism. She remembered three funeral processions up Rose Hill Cemetery to bury her husband and two of her sons. Another son, a doctor, had died young. She pulled any weeds and perhaps placed garden flowers around the headstones before she settled on a bench to knit awhile.

Grandmother had five given names, something I found quite exotic. Why five names? She never said. Baptized Thea Peterea Hansina Paulina Fredrickka Schau, she emigrated from the Jutland region of Denmark to America as a young girl, a child really, her lithe silhouette overshadowed by defiant squared shoulders and determined chin. Why did she leave Denmark? Never a word. A shifting political border with Schleswig-Holstein placed her birth in Germany in 1874, but she certainly never talked about that. She was a Dane.

Grandmother had five given names, something I found quite exotic. Why five names? She never said. Baptized Thea Peterea Hansina Paulina Fredrickka Schau, she emigrated from the Jutland region of Denmark to America as a young girl, a child really, her lithe silhouette overshadowed by defiant squared shoulders and determined chin. Why did she leave Denmark? Never a word. A shifting political border with Schleswig-Holstein placed her birth in Germany in 1874, but she certainly never talked about that. She was a Dane.

Grandmother was of the people who laid the foundation for Scandinavian democracy and who gave us author Hans Christian Anderson, philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, and the exquisite knitted nattrøjer (literally, night jackets). Danes invented nattrøjer around 1600 when the European Renaissance brought knitting to Denmark. A short blouse knitted of fine wool dyed a solid color, the nattrøjer was a complex piece of soft architecture with knit, purl, and traveling stitches worked on front and back—no rest rows for Danish knitters—creating motifs believed inspired by intricate damask weaving.

In 1893 when Grandmother married her second-generation German American husband, the genes she would commingle with his carried coded instructions from 300 years of Danish nattrøjer knitters. I like to think beyond genes that are out in the open, those genes that reveal a familiar color of eyes or hair. I like to imagine genes that lurk in genetic shadows, waiting, watching for likely offspring open to receiving a generous ration of, say, knitting genes. Genetic memory, say the anthropologists.

Grandmother and I had shared knitting history before my garter stitch knitting lessons. For my baptismal baby portrait, I was placed on her lacy, feather-and-fan knitted blanket and wore her special bootees. No baby ever kicked off those bootees, she claimed. Over the years, she knitted a snowsuit, stocking cap, and child-size afghan for me. When I was nine, she purchased and filled a traditional “hope chest” with embroidered hand towels, crocheted tablecloth and potholders, and a knitted baby layette. She also crocheted and starched a dozen nut cups, tiny baskets with handles, that she considered useful for luncheons she presumed I would host for ladies in my circle of friends. She also gave me her cut glass crystal bowls and a monogrammed sterling silver service for twelve. Grandmother foresaw my life as one of ease and elegance.

Years before she taught me to knit, Grandmother and I had shared front-page status in the February 15, 1945, edition of The Emerson Tri-County News. Me, I received a headline simply for showing up, she for civic engagement as village chair of the World War II knitting drive, the massive and coordinated effort to make and donate hand-knitted socks, sweaters, shooting mitts, scarves, bandages, and such to military troops.

Receives Red Cross Yarn

Mrs. Thea P. Moseman, local Red Cross knitting chairman, has received a shipment of 50 pounds of yarn. She urges all women who are interested in knitting for the Red Cross to call for yarn at her home.

Birth Record

Born, Tuesday, Feb. 13, to Mr. and Mrs. Harold Moseman, a daughter, in the Lutheran hospital in Sioux City.

So Grandmother and I were front-page news, but so were the high school basketball scores, the obituary of Mrs. Henry Kleinberg, the elaborate Porter-Hingst wedding, the large crowd at a dance featuring Erving Schmidt and His Rhythm Swingers, the Uptown Cafe’s successful Friday night benefit fish fry, and News of Emerson’s Men in the Service. The news-packed front page of the weekly Emerson Tri-Country Press was a nod to the excellent eyesight of 800 or so readers in Emerson.

So Grandmother and I were front-page news, but so were the high school basketball scores, the obituary of Mrs. Henry Kleinberg, the elaborate Porter-Hingst wedding, the large crowd at a dance featuring Erving Schmidt and His Rhythm Swingers, the Uptown Cafe’s successful Friday night benefit fish fry, and News of Emerson’s Men in the Service. The news-packed front page of the weekly Emerson Tri-Country Press was a nod to the excellent eyesight of 800 or so readers in Emerson.

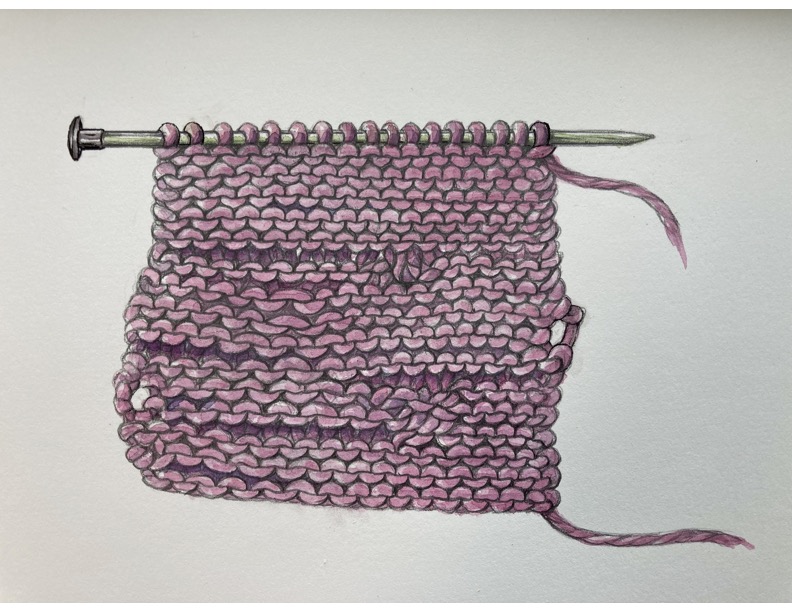

After Grandmother’s visit, my knitting shifted into classic error mode. Unsupervised, I knit four inches or so with accidental yarnovers that I knit into random eyelet openings. The width spread when I knit into both legs of a stitch at the beginning of some rows. Confusion led me to knit two stitches together now and then. Largely unaware, though I suspected something had gone awry, I concentrated on picking up and pulling loops through loops. After one intense bout with knitting, I laid my yarn and needles on the coffee table in front of our living room sofa.

When I returned, I asked my mother, “What happened to my knitting?”

“Oh, a friend came by for coffee and knitted a few rows for you. Wasn’t that nice?”

No, no, no. That was not nice. Her friend had knitted several inches of perfect garter stitch above my beginner efforts.

“But it was my knitting,” I said. Quietly.

I picked up my sad little piece of garter stitch knitting. I held it in the palms of my hands like a wounded bird, perhaps a sparrow with one perfect wing and one broken wing after flying into a window. My painstaking stitches, blessed by Grandmother, had shown promise. Now I saw a lumpy pink mess beneath the garter stitch perfection of a proficient adult knitter.

Before then, achievement had come easily for me, mostly. I was an early reader. A novice but enthusiastic Brownie Scout. My teachers liked me. And I was fearless on the slides and rides—shockingly hazardous by today’s standards—in the park across the street from our home. Teeter-totters swung high with a narrow plank and no handhold, swings had no safety belts or molded plastic seats, the thrillingly high slippery slide burned hot in the sun. I also liked riding with my father on his motorcycle—no helmets—over the surrounding gravel roads.

Most days, I rambled about on my own in the park across the street. Pedaling my blue Schwinn bicycle, I channeled an extended fantasy of Annie Oakley—my only warrior woman role model—riding her horse Target. Every week on television, I watched hard-riding, sharp-shooting Annie handle the bad guys who threatened her hometown of Diablo. I wanted to be Annie—confident, athletic, on the side of good. I braided my hair like TV Annie and asked my father for a horse.

I also roamed freely each summer during brief but much anticipated stays at the Iowa Great Lakes, a resort known locally as Okoboji. During daytime, I could explore on my own because it was a different time in the world. I rode the Tilt-a-Whirl and Bumper Cars at the amusement park. I walked narrow trails beside the lake, imagining myself in the mountains and sandstone rocks of TV Annie’s Western landscape.

My Okoboji meanderings always ended at the Gardner Log Cabin, the historic site of the 1857 “Spirit Lake Massacre.” Wide-eyed, I gawped at artifacts—rawhide bags, war clubs, portraits of victims—with morbid childish fascination. In a slender booklet—The Okoboji and Spirit Lake Massacre and Kidnapping Story, 50 cents—I read the captivity narrative of lone survivor Abigail Gardner Sharp, her story my sole brush with cultural history.

Back in Emerson, my mother’s photo albums show my childhood as a social whirl of parties, holidays, and dance recitals. The reality I remember was the gift of being on my own, alone with my thoughts when not in school and, in fact, much of my time in school. A weekly drive over gravel roads for tap dancing lessons in Sioux City, Iowa, interrupted my solitary thoughts and ramblings. Tap dancing was fun, sort of, but my heart was in piano lessons with Mrs. Lenhouts, where I perched each week on a piano bench at the grand piano in her Emerson home.

I loved learning piano from kindly Mrs. Lenhouts, a large woman with a gentle smile and soft hair. Mrs. Lenhouts understood my emerging love for music. The first classical music to reach my ears had been Beethoven’s Symphony #6, the Pastoral, in Walt Disney’s animated film Fantasia. My mind drawn to the visual, music paired with animated sorcerers, flying centaurs, and dancing mushrooms was powerful stuff. Pejorative stereotypes flew over my youthful head.

I was no piano prodigy. Rather, playing piano released emotions, experiences for which I had no words. During one lesson, Mrs. Lenhouts commented on my ponytail with permed curls secured by a tightened rubber band.

“Your hair looks very smooth today. It looks like your mother was angry with you and brushed your hair hard to make it so tight. Did that hurt?”

I shook my head no and slipped into silence, humiliated to my core. That was exactly what had happened before my lesson. I had no idea what I had done to make her angry with me. Mrs. Lenhouts was the only adult who looked deeply into my eyes and knew me. And I knew that she knew. Quietly, she turned the page to the next lesson. I hushed my pain and continued playing.

Mrs. Lenhouts was studying for an advanced degree in early childhood education, and she chose eleven-year-old me as the subject for a term paper. She administered “mentality” tests, reviewed school grades and medical history, and queried the pastor at St. Paul’s Lutheran Church and my classroom and Sunday school teachers. She interviewed my parents at home. No comments from church people found their way into her report, but my fifth-grade teacher ranked me first in the class—full disclosure, there were nine students in fifth grade—and wrote, “[Susan] does additional work eagerly and enjoy[s] special assignments.”

Mrs. Lenhouts was studying for an advanced degree in early childhood education, and she chose eleven-year-old me as the subject for a term paper. She administered “mentality” tests, reviewed school grades and medical history, and queried the pastor at St. Paul’s Lutheran Church and my classroom and Sunday school teachers. She interviewed my parents at home. No comments from church people found their way into her report, but my fifth-grade teacher ranked me first in the class—full disclosure, there were nine students in fifth grade—and wrote, “[Susan] does additional work eagerly and enjoy[s] special assignments.”

My autobiography for Mrs. Lenhouts disclosed, “I’ve always wanted to be an artist that paints or a cartoonist, or a dress designer. I think a dress designer would suit me fine.” My love for art and cloth and making by hand was apparent in the countless hours spent designing and stitching clothing for my dolls. Mrs. Lenhouts commented in the summary of her paper:

She [Susan] seems to lack a sense of freedom in her home, and social life. Perhaps she is too restricted by too many and too strict mores in her social relationships. She seems to lack confidence in herself. This needs to be built up.

Mrs. Lenhouts saw that I was an anxious child. And I had been anxious long before she wrote her report. I bit my nails, severely. I had a difficult time falling asleep. Before I learned to read, I hid the disturbing Little Golden Books about animals. Bambi. Dumbo. A terrified squirrel hiding in a coffee pot from armed and bearded hunters.

And odd things happened at home. One day I peered up from my tricycle at a lovely young woman—my father told me she was my half-sister from California—and grappled with the notion that another daughter had lived in my house across from my park, gone to my school, and had my father but a different mother. In conversations overheard at home, I learned worrisome words. Korea. Communism. Cold War. Polio. Iron lung. The trial and execution of Julius and Ethyl Rosenberg weighed heavily on my mind.

Sunday school at St. Paul’s Missouri Synod Lutheran Church up the hill from our house was a petri dish of cultured childhood fears. Bible characters in flannel board parables warned against sin. Sins of course, doomed you straight to hell. At school, emergency drills coached kids to “Duck and Cover” under desks if a Russian atomic bomb fell on Emerson. My backup plan for the Russian threat was to become a doctor. When Russia invaded, they would not kill me if I became a doctor.

And then my mother’s friend showed me I was a failure as a knitter.

I’m not any good at knitting, I thought.

There would be no garter stitch dishcloth.

I stopped knitting.

Illustrations by Susan M. Strawn

Copyright © 2022 by Susan M. Strawn

Susan M. Strawn

Knitting: a faithful, lifelong companion

Susan M. Strawn, Ph.D.

Susan has loved making cloth and clothing as long as she can remember. And knitting has been her faithful, lifelong companion.

Formerly a staff artist at Interweave Press in Loveland, Colorado, Susan’s immersion in the world of extraordinary handmade textiles led to her career as a scholar of textiles. She left Interweave to earn a doctorate in Textiles and Clothing—emphasis on historical/cultural textiles—from Iowa State University. Her dissertation examined the restoration of Navajo Churro sheep and wool to Navajo weavers. As professor of Fashion Design and Merchandising at Dominican University (Chicago), she taught historical and cultural dress, textile science, and surface design of fabric. In 2015, she stepped down as professor emerita from her tenured teaching position.

Susan’s cultural history of hand knitting—Knitting America: A Glorious History from Warm Socks to High Art (Voyageur Press, 2007)—received a first-place award from Midwest Independent Book Publishers. She is the author of more than 50 trade and juried publications, many about the history of American knitting, and is a veteran of nearly 80 invited or juried presentations. She serves as contributing editor to PieceWork, a magazine of history and needlework, and continues to discover stories held in cloth and clothing. She seeks the work of otherwise anonymous makers, knitters in particular.

Susan is currently writing a memoir, Loopy: Stories from a Knitting Life. She lives on Bainbridge Island, Washington, near her son and his family.