From Hand, Shadow, Rod:

The Story of Eulenspiegel Puppet Theatre

“I’m off!” said Teri Jean. “Wish me luck recognizing them!”

She steered the Suburban out of our driveway and off to the Cedar Rapids airport to pick up Olaf and Detlef, our guest puppeteers from Dresden, along with their wives, Sonja and Ilona. It was their first trip to the US, their first time in any West Block country apart from West Germany. In October 1993, Germany had been reunified for slightly less than three years.

In 1991 I was elected to the Board of Directors of UNIMA-USA, the American branch of Union Internationale de la Marionette. With branches in ninety countries, UNIMA is dedicated to promoting peace and understanding through the art of puppetry. Allelu Kurten, the same woman who facilitated our invitation to the East German festival, headed the American branch of the organization. She told all new Board members they should pick a project to develop and work on. She advised me to establish an informal exchange with a foreign company and use that exchange as a pilot project that would show others the way.

“This is a natural for you, Monica, with your fluent knowledge of German,” she said.

The idea intrigued me, so I turned once again to the director of UNIMA-DDR, even though that organization became defunct along with the country it represented.

Since reunification, there was only one UNIMA-Germany, not an east and a west, but I knew that he would have the contacts I sought. I sent him a letter, asking whether he knew of any small troupes – one to three people – who would be interested in an informal exchange. He passed the letter on to Olaf Bernstengel, the director of the puppet theater museum in Dresden, and Olaf, a performing puppeteer himself, seized the opportunity.

Teri Jean steered the Suburban through the tunnel of autumn-golden trees that lined my lane. She pulled up in front of my log cabin home.

“I spotted them right away!” she said. “They looked way too chic and European to be local!”

The car doors opened, and our guests stepped out. Olaf had perfectly styled and gelled dark hair and lively eyes. Sonja, his wife, tall, slim, and blonde, looked around in wonder. Was this bucolic scene – with honking geese and prancing goats – really the country she’d grown up to view as enemy territory? Detlef, blonde and stocky with twinkling eyes, crawled out of the back seat with his tiny, sweetly shy wife, Ilona.

They saw a log cabin surrounded with ten acres of woods, birdhouses fashioned out of discarded tea and coffee pots, a small garden plot surrounded by a fancy iron fence, even a gypsy wagon we’d taken to Renaissance Faires. Metal birds perched on tree stumps. Next to the house stood my workshop, a bright red repurposed semi-trailer. A few steps away stood John’s workshop – yellow, red, and blue – flanked by two of his favorite finds: a railroad signal and a traffic light. He’d switched the light to green to welcome our guests. They stood agape, then relaxed and grinned.

Schulz here: Boy, do you remember their first rural Iowa experience? They put down their suitcases to shake hands, and Clover and Dandelion, our rascally pygmy goats, attacked their suitcases and ate the airline tags! We knew they were cool when they laughed instead of getting all bent out of shape! *

Schulz here: Boy, do you remember their first rural Iowa experience? They put down their suitcases to shake hands, and Clover and Dandelion, our rascally pygmy goats, attacked their suitcases and ate the airline tags! We knew they were cool when they laughed instead of getting all bent out of shape! *

In planning their visit, we intended to expose them, as much as possible, to the range of American puppetry. We represented the mainstream: family and school shows. We had put our own work on hold and become their roadies for the duration of their visit, but we scheduled a performance of Hansel and Goosel—our adaptation of Hansel and Gretel with goslings in the title roles and a fox in the role of the witch – so they could see us perform for a school audience. They loved hearing the giggles and squeals as much as we did.

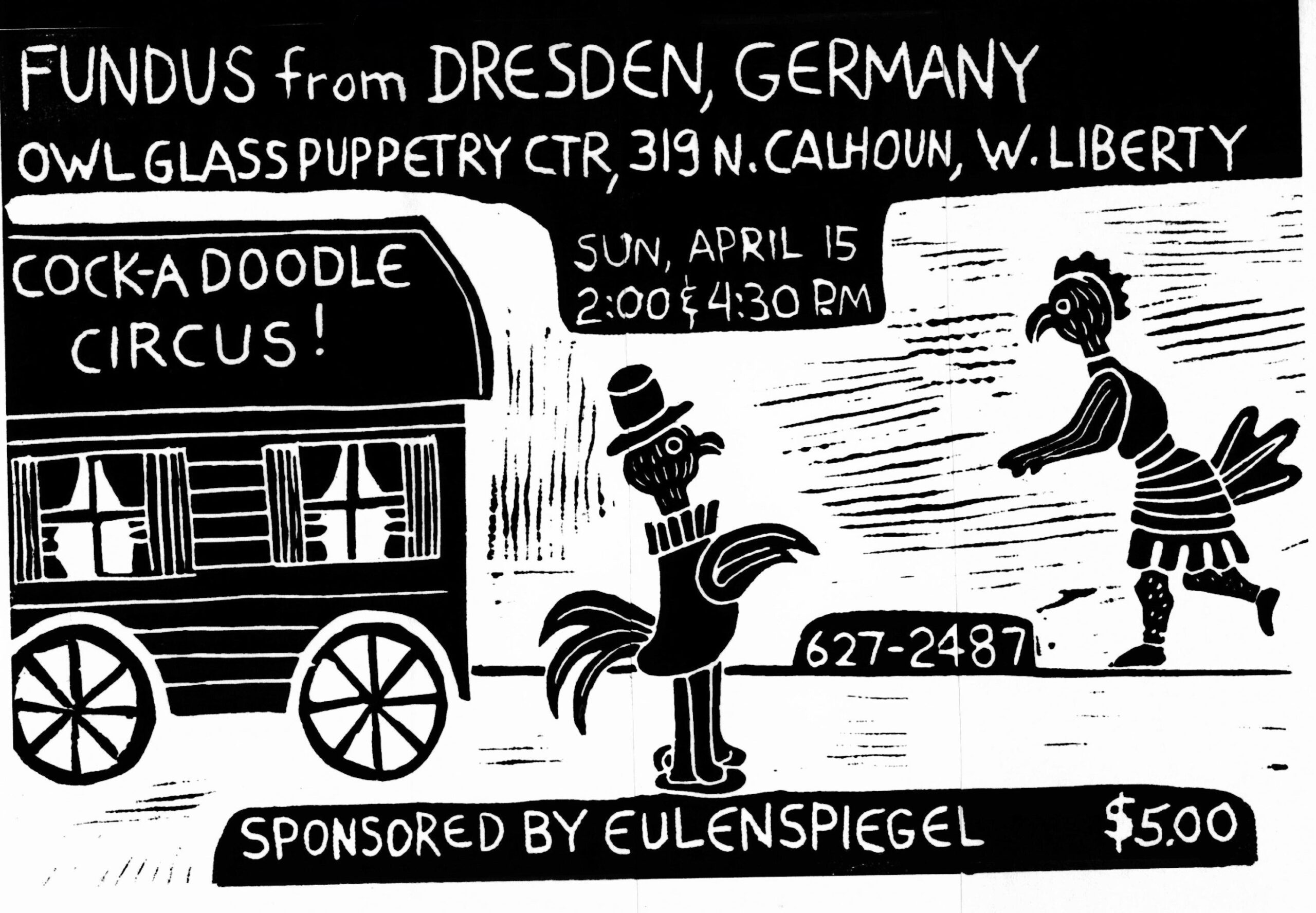

Olaf and Detlef’s production was a 19th-century marionette variety show using beautifully crafted copies of the original marionettes. The stars of the show were “trick marionettes,” constructed and strung to do one specific thing – walk a tightrope, perform acrobatics, juggle. The piéce de résistance was the breakaway skeleton whose bones separate and seem to fly into the audience. Olaf and Detlef, in red satin vests and black bowler hats, acted as the 19th-century proprietors, firing repartee at each other and the audience. The marionettes were beautifully crafted and manipulated and drew gasps from the audience, and the chemistry between the puppeteers kept the show moving.

We wanted our Dresden friends to see how this 19th-century German art was reinterpreted in 20th-century USA, so we rented a car and sent them off to St. Louis where we’d scheduled them to perform for the St. Louis Puppetry Guild. We made sure they’d meet Bob and Dug of the Kramer Marionettes. Their puppets were technically similar to Olaf’s – acrobats, skaters, dancers – but the aesthetic was completely different. Olaf and Detlef’s characters were hand-carved copies of the originals; Bob and Dug’s looked distinctly American. Teri Jean prepared them.

“Just wait. You’ll think you’re watching a drag show. The costumes are fabulous! Satin, sequins, feather boas! Fantastic puppet hairstyles! Like watching the best ever fashion show!”

After seeing the show, they compared notes on construction and stringing and marveled at their similarities – and their differences.

To round out their experience, we wanted Olaf and company to see a politically charged show. Puppet theater, because it deals in metaphor and parable, can be an effective force for change. In the Heart of the Beast Puppet and Mask Theater in Minneapolis embodies this idea with strong stories and evocative visuals, specializing in giant parade-sized puppets. Their work often centers on environmental problems and issues of hate and divisiveness. They had recently opened Befriended by the Enemy, the true story of a grand dragon in the Ku Klux Klan, and the Jewish neighbors who responded to his messages of hate with compassion and offers of help, transforming all of their lives. The show opens with parade-size angels – long necks evoking Giacometti sculptures – coming through the audience. The story is mesmerizing and served as a perfect foil to the Kramer marionette show.

In between St. Louis and Minneapolis, we toured them and their show around Iowa during the most beautiful fall I can remember – endless sunny days, brilliant foliage, flocks of honking geese heading south, and the aroma of burning leaves. Rural Iowa was not what television had led these German city children to expect from their American adventure! They imagined rampant consumerism, neon lights, and fast cars. Instead, they found sleepy small towns and occasional tractors and combines keeping traffic at a snail’s pace.

“I love these little schools! They’re like community centers!” enthused Sonja. “And the libraries! Even the tiniest towns have one!”

“Look! There’s no one on the road but us!” added Detlef, accustomed to the city traffic in Dresden.

Small-town cafés had begun offering salad bars. Our guests loved them! Such an abundance of fresh food, and each one was different. Some focused on healthy green salads with raw vegetable toppings, and some were more like rural potlucks, with mayonnaise-rich macaroni salads, fruit-encrusted jello, and herring in cream sauce.

“Is your life always this relaxed?” asked Olaf. Little did he know how hectic the planning and finalizing of their tour had been – hundreds of phone calls, visits with our Senator’s aide to check the legality of what we were doing, and acquisition of the sound equipment they needed for their show.

Everyone loved their show! Olaf had gotten his Ph.D. in history, writing his thesis about traveling puppet theaters in Saxony in the 18th and 19th centuries. His knowledge of the puppetry of his homeland, the countryside around Dresden, was extensive. He was the director of a puppet theater museum that had received a donation of 19th-century variety marionettes, and he couldn’t resist playing with them and demonstrating them for tour groups visiting the museum. He had them copied by a local marionette builder and enlisted Detlef, the grandson of their original owner, to join him in creating a show that was whimsical, funny, and engaging.

Schulz again: I remember one part of the show! They had a juggler with gold juggling balls, and Olaf introduced him as the man with the two golden balls. Howls of laughter from the grown-ups! You guys were mean – you never told him what was so funny till the end of the tour. Luckily, Olaf thought it was funny, too.

One day we took them to the elementary school in Jesup, Iowa. After the show, the art teacher asked if we wanted to join him as he made his weekly visit to the nearby Amish school, a one-room schoolhouse out in the country. We jumped at the chance! We were quite familiar with their culture, living so close to a large Amish settlement, but our German guests had never heard of contemporary groups living without electricity or motor vehicles and dressing in 19th-century garb. They were thrilled to be invited!

We entered the white clapboard one-room schoolhouse and were transported back to the era the puppets had inhabited. The children—twenty or so of various ages—looked as 19th century as the puppets did, with their long dresses, braids, suspenders, and bowl haircuts. They sat on rows of benches, eyes wide.

We entered the white clapboard one-room schoolhouse and were transported back to the era the puppets had inhabited. The children—twenty or so of various ages—looked as 19th century as the puppets did, with their long dresses, braids, suspenders, and bowl haircuts. They sat on rows of benches, eyes wide.

Olaf and Detlef got out a few of their favorite marionettes to show. These kids had never seen puppets of any kind, much less multi-string marionettes that could juggle, walk a tightrope, and perform acrobatics! Gasps and giggles filled the room. When question time came, Olaf, having heard them speak to each other in a German dialect, decided to talk to them in his native tongue.

“Guten Tag, Kinder! Die Marionetten sind schön, nicht wahr?” (Good day, children! The marionettes are beautiful, aren’t they?”)

No response.

“Hmm,” said Olaf. “Maybe I should try my Saxon dialect.”

“Güd’n Dag, Geender! Die Marionedd’n seend schane, neescht wahr?”

Excitement reigned, and all of the kids clamored to talk to Olaf in what sounded an awful lot like Saxon! The excitement only heightened as Olaf let a few kids try working the marionettes.

The first boy held the control gingerly, barely breathing, not sure what to do with it. Olaf stood next to him, guiding his hand to hold the puppet high enough that the legs straightened, and the feet caressed the floor. He showed him how to tip the control back and forth to make the puppet walk. Others clamored for a turn.

When we finally left, they all followed us outside and waved as we drove away.

On November 14, it was time to say goodbye. We awoke to a gray, drizzly day – the first since they had arrived that wasn’t gloriously sunny – and packed the Suburban for the trip to the Cedar Rapids airport. Teri Jean brought a bottle of champagne along. We sat in the airport, toasted each other as champagne fizzed on our tongues, and agreed to meet in a year in Germany. We bade our new friends goodbye and drove home in freezing rain. The magical interlude was over.

A year later, in September 1994, we found ourselves in an airport once again, this time the Chicago airport, to take Delta Airlines to Berlin. Teri Jean had quit smoking years earlier and, like many former smokers, had developed a severe allergy to cigarette smoke.

“I wish we could have found a smoke-free flight,” she moaned. “This is torture! Non-smoking section, ha! The smoke doesn’t know it’s supposed to stay back there!”

Cousin Hermann met us at the Berlin airport and took us home for tea. Teri Jean promptly crashed and spent the rest of the day sleeping off the smoke hangover. We spent the next couple of days wandering around Berlin, east and west. It felt surreal to be able to go where we pleased with no checkpoints. The areas where the wall had been either looked like war zones, with remnants of the wall still standing, or like construction sites, with scaffolding and cranes, very much in transition.

I thought back to my art school days when I loved visiting my East Berlin cousins and once spent an entire month with them. I would arrive at Checkpoint Charlie where Americans crossed the border and submit to a search of my bags. I always carried forbidden items – a West German news magazine, a sought-after book – stashed away beneath dirty underwear. On the other side, I’d see my cousin’s children waiting for me: Eva, just four years my junior, Benita, and the twins Friedemann and Sabine, ten years younger than me. When my visit ended, the kids walked with me back to the checkpoint, seven blocks from their home. Suddenly I could cross wherever I wanted, and Friedemann – whose baby daughter Johanne was my godchild – came along!

On the third day, Olaf and Detlef came from Dresden to drive us and the puppets to our first show. We arrived in Hohnstein, a lovely little village crowned by a medieval castle, facing the Elbe River. Hohnstein was the home of the Kaspar Kino, the resident puppet theater of the Hohnstein Kasperles, the most traditional of hand-carved hand puppets, the wooden cousins of the paper-mâché puppets I had grown up with.

The show we brought, Tails From Africa, was very different from the shows usually seen in the Kaspar Kino, time-honored fairy tales performed with hand puppets. Ours was a tabletop show, with handheld puppets and rod marionettes that resembled stuffed animals. The stories were African folktales, different in subject and structure from the German and eastern European fairy tales that the eastern German audiences were accustomed to.

The show we brought, Tails From Africa, was very different from the shows usually seen in the Kaspar Kino, time-honored fairy tales performed with hand puppets. Ours was a tabletop show, with handheld puppets and rod marionettes that resembled stuffed animals. The stories were African folktales, different in subject and structure from the German and eastern European fairy tales that the eastern German audiences were accustomed to.

We created the show at the request of a Ghanaian fiber artist who lived in Iowa City. Teri Jean and I both admired her work and bought her batiked fabrics.

“Why don’t you do a show of African folktales?” she asked us.

“I don’t know if I feel comfortable going that far away from my own cultural heritage,” I replied.

“If there were an African puppet troupe in Iowa, I would be asking them.”

Unassailable logic! She said that she and her husband, a folklorist, would help us choose and interpret the tales. We ended up with a group of three stories: Anansi and Tortoise, The Leopard and the Monkeys, and The Caterpillar and the Wild Animals, all trickster tales. The folklorist told us that African storytellers add details relevant to their own lives. He advised us to do the same, keeping the spirit of African storytelling instead of trying to copy it.

“You’re not African,” he said. “Trying to create an ‘African’ show would be completely inauthentic. Keep the spirit by making the stories yours.”

Tails From Africa became one of our most popular shows of all time. Although we last did the show in 2006, people still remember Cachinata the caterpillar’s boast:

“I am Cachinata, warrior son of the long one. I crush wild animals to the earth and make cows’ dung of their entrails. I am invincible!”

Or, translated to German: “Ich bin Cachinata, Krieger Sohn des Langen. Ich zermalme wilde Tiere und mache Kuhfladen aus ihren Eingeweiden. Ich bin unbesiegbar!” Translating that was one of my proudest moments!

We decided this was the show to take to Germany for purely practical reasons.

We could pack the puppets and props into two large suitcases, and Olaf could provide the right size tables. I could translate it so that I had most of the speaking parts, and I could teach Teri Jean how to pronounce hers in German. We did not anticipate how controversial it would be in a country that had, till recently, been part of an insular East Block that drew all of its cultural references from Germanic and Eastern European traditions.

The audiences were large, good, and receptive. The children, like children everywhere, got sucked into the stories and giggled at the silly monkeys, the greedy spider, and the self-important caterpillar. Just like American children, they left singing Anansi’s song.

“Mine, mine, it’s all mine, it’s all mine

Everything I covet, when I eat, I love it!” became

“Meins, meins, Alles meins, Alles meins

Alles gute Essen will ich gierig fressen”

Many of the adults saw things a little differently:

“It was a good show, but those aren’t real fairy tales.”

“I’m glad my children got to see this show. It’s good for them to be exposed to other cultures!”

“I’ve never heard stories quite like these.”

You’d think, having spent as much time in East Germany as I had, that these reactions would not have taken me by surprise. They did. I realized how much of our reality and reactions are tied up in our personal histories.

The eastern German fall that year was glorious, a match for the beautiful Iowa fall of the year before. In many ways, our experience was just as strange and enlightening as their Iowa experience had been. I had spent plenty of time in Germany – both east and west – over the years but witnessing this new culture – east and west combined – emerge from its cocoon was astonishing. Unlike Berlin, this far eastern part of the country – spitting distance from Poland and the Czech Republic – had little exposure to western ways. Many people living there, even those critical of their government, believed in the system at its core. After all, they had all heard of the homeless problems in the U.S. and other capitalist countries, a problem that didn’t exist in East Germany.

Many East Germans were repelled by out-of-control capitalism and proud of their own frugality. All of Germany was ahead of the U.S. in recycling, but East Germany was way ahead. I visited my cousin Benita. We shared a chocolate bar. When we finished, Benita looked at the foil wrapper and began to cry.

“What’s wrong?” I asked.

“I used to be able to recycle foil, now I have to throw it away.”

Most hoped that the newly reunited country would draw from both systems and combine their best elements. It didn’t turn out that way. West Germany was, after all, the victor, and “to the victor go the spoils.”

“The only thing left of our system is right turn on red,” grumbled Olaf.

Reunification cost Olaf his job. The museum he directed was government-supported, and Olaf was a civil servant. As such, he was required to meet with the Stasi – the secret police – several times a year. He was expected to report any activities or speech critical of the government. These meetings – even though he never reported anyone – were enough to disqualify him from a job in the new government, and the director job went to a westerner. Sonja’s job, as an archivist in the rare books division of the Dresden Library, also went to a westerner.

Reunification cost Olaf his job. The museum he directed was government-supported, and Olaf was a civil servant. As such, he was required to meet with the Stasi – the secret police – several times a year. He was expected to report any activities or speech critical of the government. These meetings – even though he never reported anyone – were enough to disqualify him from a job in the new government, and the director job went to a westerner. Sonja’s job, as an archivist in the rare books division of the Dresden Library, also went to a westerner.

Olaf became a full-time freelance puppeteer and Sonja worked as a freelance editor. Like all of their cohorts, they had to learn to function in a market economy, which Olaf did with relative success.

He was good at networking and had connections all over his region. He found us gigs at puppet theaters, museums, preschools, outdoor festivals, even a water mill.

The Zchoner Mühle (Mill) was a functioning watermill and a regional historical museum. It served as the home base for the Dombrovsky Marionettes, the last of the traditional traveling marionette troupes that had toured the countryside in caravans in the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth centuries. The Dombrovsky family lived here in the winter in two caravans – one for the parents and one for the daughter and her young family. They had a table and chairs outdoors between their homes where they served us coffee and conversation. The talk centered around the usual – making a living as puppeteers in the market economy.

“How do you make a living? Does your government help?” they asked us.

We told them about our school residencies, our shows at festivals and libraries, the ways we kept our expenses low and patched together each month’s income, and the ways we advertised and booked our shows.

“The state government helps with our school residencies,” I said, “but who knows how long that will last. The others, well, if they want a show, they have to figure out how to pay for it. Every year we have to reevaluate.”

“Isn’t that stressful?”

Teri Jean nodded as I said, “We’re used to it.”

“Our expenses are much higher than they used to be. So many things that were free or cheap under the old system are costly. Of course, we can get things we couldn’t get before – this delicious coffee, for instance – but we have to have the money,” they replied.

In the summers, the Dombrovskys traveled from town to town and set up in hotel courtyards where they hoped they would continue to cover their living expenses. In the winter, they were here, performing in a luxurious heated tent with a curtained stage and rows of chairs, dependent on ticket sales for their income. We performed in the morning, for a small but enthusiastic audience.

In the evening we returned to watch their adult show. The show was reminiscent of a nineteenth-century stage play – large-scale marionettes stiffly declaiming their lines in much the way their human counterparts had. The post-show, also traditional, featured a pair of variety marionettes playing the piano and dancing. It gave us insight into Olaf and Detlef’s show. A variety show – like the one they had brought to Iowa – was really a collection of encore pieces from nineteenth-century plays.

I asked Olaf if they could get an ongoing gig at a museum.

“After all, they’re living history!” I enthused.

“Oh! Don’t say that in front of them! They hate that idea! They would never do that!”

“But why not?” I asked. “It seems natural!”

“They think their work is current and relevant. They wouldn’t buy into the living history idea, even if it did increase their income.”

Eight years later, during another eastern German tour, it appeared they had changed their minds. After we performed in the puppet theater museum in the spa town of Bad Liebenwerda, the director showed us their newly renovated exhibits. One room contained a beautifully painted proscenium marionette stage installed for the Dombrovsky Marionettes. I was happy to see evidence of a little more security for our friends.

Rolf Mäser, who had connected us with Olaf, invited us all for dinner one day. His garden, like so many German gardens, was a riot of fragrant and colorful flowers. Deep red roses, blue bachelor buttons, red and yellow gaillardia, feathery stalks of goldenrod, and pink and purple cosmos competed for space.

Frau Mäser, a typical old-school German “hausfrau” fed us solyanka, a deliciously sour Russian soup; boar roast – Herr Mäser was a hunter; sweet and sour red cabbage; potatoes; and dry white wine from Dresden. A typical meal for this part of the country, she topped it off with plum cake and apple cake. We thanked Herr Mäser for the many connections he had given us (and hoped fervently that he felt our shows had been worthy of his trust).

Several of our gigs were in “Kulturhäuser” – Culture Houses – another remnant of East German culture that has largely disappeared. Many towns had a Kulturhäus – a cozy meeting place with a bar in the back, chairs, and tables, and a stage in the front. Grandmas and grandpas sipped beer and ate sausages in the back, while their grandkids sat in the front, watching Tortoise outsmart Anansi the Spider.

One Saturday we were scheduled as part of an afternoon of music and theater. Outside of the Kulturhäus, a large group of teens killed time till the late afternoon rock band arrived. With some trepidation, we talked them into coming inside for the puppet show. They turned out to be our best audience of all, hooting and hollering at Anansi the Spider’s antics, and Leopard’s frantic attempts to catch and eat the monkeys.

That evening our gig was in a restaurant performing hall, a common feature in that region. Elisabeth, a young puppeteer having career problems, attended the show and invited us to her studio to talk shop and dispense advice. Her studio was located in a half-ruined old castle surrounded by woods.

The night was dark – just a sliver of a moon peeking through the trees. We noticed a covered wagon parked in front of the broken-down castle wall. As we waited for Elisabeth to get her keys, we encountered a diminutive man, bearded, wearing a battered hat and a dark wool coat. He greeted us.

“Grüss Gott!”

The typical southern German greeting – loosely translated “God bless” – put me at ease.

“Don’t be afraid. I live in this wagon.”

I felt transported into a Grimm’s fairy tale, talking to a gnome in the woods. He was one of the many displaced by reunification. With cynical good humor, he outlined his career path before and after. He hadn’t always lived in a wagon; his post-unification income required downsizing.

The fairy tale image stayed with me as we wandered through the echoey halls of the castle until we saw a crack of light under a door and entered Elisabeth’s cozy studio. She bemoaned her failure to find consistent artistic partners and good marionette string. Unable to help her with the former, we sent her good marionette string (black braided fishline) as soon as we returned home.

The air crackled with energy during this first eastern German tour. Despite the angst and uncertainty, joie de vivre and anticipation filled the atmosphere. No one knew exactly how things would turn out. Dreams could come true. New adventures were on the horizon. We performed at two outdoor festivals that were right out of 60’s U.S.A., with craft booths, impromptu performances, spur-of-the-moment parades, and the aroma of forbidden substances.

“This could never have happened before!” exclaimed Sonja.

We spent one of our last days wandering around the Old City of Dresden. I recognized the square where I had watched the miniature marionette show that so deeply influenced my artistic vision. Construction was in progress everywhere as crews rebuilt Gothic structures bombed out during World War Two. They had been left standing, skeletal buildings with stone in some places and “bones” of reinforcing rods in others. British and American firebombs had destroyed Dresden in February 1945, after the war had – for all practical purposes – been won. A photographic display of notes people had left in public places – in hopes their missing near and dear would see them – brought tears:

“Fritzi, if you see this, meet me at Gertrude’s house. Our house is gone.”

“Bärbel, I am alive and waiting for you at our bombed-out house.”

Two years earlier, in 1992, I had visited Berlin for the baptism of my godchild Johanne, our family’s first post-reunification baby. Her great-grandmother set the table for a typical get-together: filter coffee; cake featuring plums cut in half and laid out on a slightly sweet, yeasty crust; streusel cake with a crunchy brown sugar topping; and a large bowl of whipped cream. I sipped my rich, creamy coffee, and asked, “How is reunification going for you?”

“I’m getting used to losing everything,” she replied. “After World War One, our money was devalued, and we had to start over. After World War Two, we were the international pariah, our money was devalued, and the Russians took our country. And now, our money is devalued and we’re the pariah again as the West Germans take our jobs.”

I asked Johanne’s grandfather, my cousin Peter, what he thought.

“I wouldn’t go back,” he said. “I like being able to travel where I want. I like not having to worry about expressing my opinions in public. But I miss the simplicity and the slower pace.”

It was the first of many performing trips to Germany and Austria, most organized by Olaf. It remains the most memorable. Witnessing the transition from East Bloc to West Bloc and the impact it had on my relatives and my professional peers, was a once-in-a-lifetime privilege.

Just so you know: the only reason I’m not weighing in here is that I didn’t get to go along! Someone had to stay home and take care of things here, and besides, the airlines had gotten a lot stingier about how much luggage you could take. Can you imagine? I was considered luggage!

* Schulz was the head puppet. “He called the shots,” said Monica. He is featured in the first small graphic above, holding two hand puppets, coincidentally named Monica and Teri.

Hand, Shadow, Rod: The Story of Eulenspiegel Puppet Theatre, by Monica Leo, will be published in October 2023 by Ice Cube Press. This chapter is printed by permission. Graphics courtesy of Monica Leo. Copyright © 2023 by Monica Leo.

Monica Leo

Hand, Shadow, Rod

Monica Leo is a first generation American, born to German refugees in the waning days of World War II. After the war, her parents ordered a set of Kasperle hand puppets from a German craftswomen, and Leo began telling stories with puppets. A graduate of the University of Iowa with a major in art and a minor in English, she studied for two years at the State Art Academy in Düsseldorf, Germany, with Joseph Beuys.

Since 1975, Leo has been creating and performing as founder and principal puppeteer of Eulenspiegel Puppet Theatre. Eulenspiegel’s home is Owl Glass Puppetry Center, a regional puppetry center in West Liberty, Iowa.

Since 2005, Leo has written the Scene Between column for The Puppetry Journal, a national quarterly magazine produced by Puppeteers of America. She has written for the Wapsipinicon Almanac and writes the plays for Eulenspiegel Puppet Theatre. Leo illustrated Marcel and the Dirtball, by Anne Leo Ellis, published by the Pterodactyl Press in 2002. Her memoir, Hand, Shadow, Rod, will be published by Ice Cube Press in October 2023.