Baba’s Paska: Easter 1974

The smell of yeasty dough carries me back to my grandmother’s home in Montclair, New Jersey. My sister and I enter through the back door and walk into the living room to find our Baba sitting in her red velvet wingback chair. A lighted magnifying glass illuminates a needlepoint canvas stretched on a wooden stand.

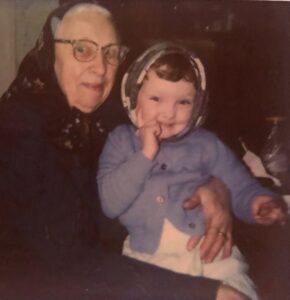

Baba wears a simple, short-sleeved navy blue dress over her stocky frame. A paisley kerchief covers her head. Her long white hair is gathered in a loose bun. Secured by a silk cord, her silver framed eyeglasses rest on her ample bosom.

She raises her beaming face to receive our greeting, a kiss on each soft rosy cheek.

Baba rises from her chair and we follow her into the kitchen. She opens the window and pours a generous handful of black oil sunflower seeds onto the glossy white sill.

Baba rises from her chair and we follow her into the kitchen. She opens the window and pours a generous handful of black oil sunflower seeds onto the glossy white sill.

“Sasha! Sasha!” she calls in the direction of an evergreen. Soon the song of a brilliant cardinal answers and he perches at the open window to enjoy his meal and Baba’s praise.

“Lyuba, lyuba ptashechko.” Her voice sings just as brightly as her dear little bird. Once her bird flies away, Baba closes the window and turns her attention to the sweet dough into which she has folded plump golden raisins and waited for it to double in size.

A warm and tangy scent emanates from the cloth-covered bowl. Baba turns the shiny dough out onto the floured table, divides it evenly, slides the loaves into greased and floured coffee cans, and brushes the tops with egg wash. Into the oven go the paska, the traditional bread made to celebrate the Ukrainian Orthodox Easter.

Once the domes of baked bread have cooled, Baba decorates each top with royal icing, rainbow nonpareils, and an XB in bold red letters.

When I ask Baba what the initials X and B stand for, she chuckles softly, looks at me with her icy-blue eyes, and explains that the Cyrillic letters Chuh and Vuh stand for “Khrystos voskres” which means “Christ is risen!”

My sister and I stumble over the traditional response to this Easter greeting, “Voistynu voskrese!” (Indeed, He is risen!)

We fill the woven basket we will bring to church for the midnight liturgy: hard boiled eggs dyed golden brown and etched with simple geometric patterns, kielbasa, salt pork, cheeses and the paska. Baba covers these delicacies with a long white embroidered cloth.

Baba has changed into a lavender dress, a bright floral kerchief tied around her head. Her lilac eau de cologne wafts through the air as we make our way into the candlelit church.

My senses fill with incense, chanting, icons in gilded frames. Parishioners stand, women with heads covered on one side of the church, men with hats in their hands on the opposite side. When the choir chants “Hospody, Pomyluy” (Lord, Have Mercy), Baba crosses herself three times, slowly bending on sturdy legs to touch the floor.

Returning to Baba’s house after the hours-long service, Baba tucks my sister and me into a warm, downy featherbed. Lace curtains billow in a gentle breeze.

Soon uncles, aunts and cousins will join Baba in breaking her Lenten fast. We will come together around a table adorned with vases filled with daffodils, forsythia, and pussy willows to enjoy a feast of roasted lamb, kielbasa, salt pork, cheeses and hard-boiled eggs and paska.

But now my sister and I fall gently to sleep as birds begin to wake. The tick tock of the grandfather clock marks time with the rising dawn chorus.

Listen to Annette read Baba’s Paska: Easter 1974:

Oma’s Cherry Varenyky: Love in Tiny Packages

The branches of our cherry tree, so heavy this Spring with vivid white blossoms, now bend under the weight of plump rose-blushing cherries.

I climb a sturdy step ladder up into the canopy. My grandmother has tied a clothesline cord around the handles of a stockpot. At the top of the ladder, I drape the cord over my head. With the pot hanging just below my chest, I have both hands free for picking fruit and sampling a few cherries. Their firm yellow flesh is tangy.

Even with all my sampling, it doesn’t take long to fill the pot. I climb down the ladder and carry my harvest up a winding staircase to the 2nd floor apartment of my parents’ home.

Standing over a steaming mixture on the stove, my grandmother pushes her dark cat-eye glasses up to the bridge of her nose. Oma will strain the cooked cherries through cheesecloth into glass milk bottles. My siblings and I will freeze some of the juice in metal ice cube trays. All summer long, after full days of stickball, bike riding, and roller skating, we’ll quench our thirst with bright cherry slushies.

Standing over a steaming mixture on the stove, my grandmother pushes her dark cat-eye glasses up to the bridge of her nose. Oma will strain the cooked cherries through cheesecloth into glass milk bottles. My siblings and I will freeze some of the juice in metal ice cube trays. All summer long, after full days of stickball, bike riding, and roller skating, we’ll quench our thirst with bright cherry slushies.

I carry the latest harvest over to the sink and fill the pot with cold water, watching the fruit bob and turn. After a thorough rinsing, we stem the fruit and place them in a large pink pyrex bowl.

Oma makes varenyky dough with flour, eggs, vegetable oil and salt. She rolls it out on the floured table and hands me a flour-rimmed glass to cut the thin dough into rounds.

We fold each round of dough over a spoonful of cherries, pinching the ends firmly. As we make the dumplings, my grandmother, unlike my mother, tells me stories about her life in Ukraine.

When Oma was 17, my grandfather came to visit family in Neu Danzig, a German village near the Black Sea in southern Ukraine. One day, my grandfather, a shipbuilder who was 8 years her senior, came to the house and spoke with her father. Even though my grandmother had older sisters, my grandfather said he was impressed with her and felt sure she would make a good wife and mother.

“The morning after our wedding,” Oma recalls, “I woke early in the dark to prepare breakfast for my husband. I tried to boil eggs. But no matter how long I cooked them, they wouldn’t get any softer!”

Chuckling to herself, Oma rises from her chair and moves to the stove with the platter of dumplings. She adds them one at a time into a pot of simmering water.

“When I heard your grandfather coming down the stairs, I sat down at the table and hid my face in my apron.”

Fishing out the dumplings, she sets them on a folded cotton cloth to drain.

“But I needn’t have worried.” Here Oma takes both of my hands into her own. She brings her face close to mine. “Your grandfather took both of my hands into his own and he said, ‘Come. Let us make breakfast together.’” She smiles wistfully and squeezes my hands. I squeeze hers back before she lets go.

Oma pours nutty browned butter over a plateful of varenyky. She sprinkles cane sugar on top and sets the dumplings in front of me. As I bring the first forkful to my mouth, she kisses me three times on the head.

Listen to Annette read Oma’s Cherry Varenyky:

My Father’s Eggs and Onions: There’s an Ogre in the Kitchen

I remember waking some weekend mornings to the sound of a sharp knife slicing crisp onions. I roll out of bed, pad down the hall and into the kitchen to watch my father make his one and only culinary masterpiece, eggs with sautéed onions. On these rare occasions, I help him prepare his signature dish and listen to stories about his childhood in Ukraine.

My father, who was born in northern Ukraine in 1928, sets a sweet Vidalia onion on a cutting board in front of me. As I peel away its leathery outer skin, I learn that as a little boy, my father moved with his mother, father and older sister to an industrial city on the Dnieper River in central Ukraine. By 1933, my father had survived polio and the Holodomor, the two-year famine orchestrated by Joseph Stalin which claimed the lives of more than four million Ukrainian people, old and young.

During that famine, my father carried home a dead catfish after the flood waters receded. He was so young that the fish was almost as big as he was. He was so proud thinking he could provide for his mother and sister while his own father worked in a labor camp in Siberia. On the first anniversary of my father’s death, my grandmother Baba recalled through tears how she had scolded him for bringing that dead fish into her kitchen.

Back in my parents’ kitchen, my father teaches me how to cut onions into thin slices. He guides my hand, instructing me to let the weight of the blade shear rather than saw through its layers.

My father adds sweet cream butter to a skillet. As the butter melts, he continues his story.

My father adds sweet cream butter to a skillet. As the butter melts, he continues his story.

After World War II, my father tells me, he left Ukraine with his family and sought refuge in a displaced persons camp in southeast Germany. There, he went to a non-classical secondary school, struggled to learn English, and worked in a United States Army kitchen “peeling potatoes,” he recounts with a smirk.

Arriving in America in 1951 with a limited knowledge of English, my father progressed through a civil engineering program, earning a Master of Science in 1957. For him, math was a universal language. “If you understand math,” he explains, “You can speak with anyone in the world.”

Tilting the skillet to evenly distribute the butter, my father places handful after handful of the thinly sliced onions into the pan and cooks them slowly, patiently, until they are sweet and tender. As the translucent crescents begin to brown, he lowers the heat and seasons them with salt.

Early every workday morning for more than 20 years, my father boarded the 66 DeCamp bus. Alongside his hand-drawn plans for the renovation of Yankee Stadium or the design for Giants Stadium, he slid into his attaché case a paperback copy of Samuel R. Delaney and The New York Times chess column for the long commute into Manhattan. On those weekday mornings, he would drink a cup of instant coffee before dashing up the block to catch his bus.

But this morning, he sips hot freshly perked coffee while standing beside the stove. To loosen the flavorful caramelized bits from the pan, my father pours in a generous amount of cognac, measured by eye. With a wooden spoon, he forms nests into the bed of sauteed onions to cradle the eggs and poach them in that fragrant liquid.

Many years later, after enjoying a plateful of eggs and onions, my father scoops up his 3-year-old granddaughter and sets her in his lap. Pretending to be an ogre, he teases her about making her into rich and tasty stew.

Taking my daughter’s arm, he growls playfully, “I chop, chop, chop the onions.” Pretending to chop her arm from shoulder to wrist, he rumbles, “I chop, chop, chop the potatoes.” Shaking his head from side to side so that his jowls wag, he quakes, “And I chop, chop, chop the salt and pepper.”

On cue, my daughter giggles, crinkles her tiny nose, and declares, “Didu! You can’t chop, chop, chop the salt and pepper!”

She wriggles down from her grandfather’s lap and runs to squeeze beside her Oma cradling her sleeping infant brother.

My father, grinning, looks at me over his glasses and sings in his rich baritone: ”Ochi chyornye, ochi zhguchie, Ochi strastnye i prekrasnye.”

I imagine I can hear the strumming of a folk guitar.

Listen to Annette read My Father’s Eggs and Onions:

My Mother’s Red Borscht: A Bowl of Childhood Memories

My mother always asks me what special dish I’d like her to prepare for my homecoming. It is winter and I am visiting from Iowa over a school holiday. I request red borscht, but this time I ask that we make it together.

A stockpot simmers on the stovetop. Well-marbled hunks of chuck roast transform tap water into a rich broth. My mother’s kitchen is filled with its aroma.

A stockpot simmers on the stovetop. Well-marbled hunks of chuck roast transform tap water into a rich broth. My mother’s kitchen is filled with its aroma.

We sit together at a table laden with an abundant harvest: Idaho potatoes, green cabbage, carrots, leeks, and crimson beets. I peel and grate carrots. My mother quarters and chops cabbage.

“I remember,” my mother begins, “when I was a little girl, my mother and I would sing together while we worked around the house.”

“What songs would you sing?” I ask brightly, hoping to encourage my mother to share details about a childhood she rarely talks about.

“Hymns mostly, I suppose. I can’t remember now.”

“So nimm denn meine Hände?” I prompt, recalling this hymn is one of my mother’s favorites.

My mother doesn’t answer. She seems to be deep in thought as she peels the beets. Some of these beets she will shred with the box grater, others she will cut into large chunks.

“You need to put the potatoes first in the pot to cook,” she instructs after several minutes pass. “So that they won’t turn bright pink when you add the beets.”

We add the cubed vegetables and cover the 20-quart stockpot with a cookie sheet, the pot’s cover having been misplaced ages ago. Just before serving, we will add the shredded carrots and beets along with a recent addition to the family recipe, two cans of white cannellini beans.

Ladling generous helpings of borscht into two bowls, my mother returns to the table and her story.

“Before the war, my mother would ask me what I’d like to eat: piroshky, halusky, or something else. And I would pout. And I would sigh. And I would answer, ‘I can’t decide.’” Looking down at her bowl, my mother scowls and continues, “How foolish I was! When I think of all that I had that I took for granted.”

“During the war, food was rationed. So many kilos of flour, so many grams of butter, and only 6 eggs! Often my mother would not eat to make sure we had enough.” She sighs ruefully and shakes her head, dismissing her self-reproach.

Then looking at me with bright blue eyes, my mother begins a story I have heard many times and now cherish.

“Once when  I was very sick, I remember lying in my bed. Our neighbor was making borscht and the aroma drifted into my room from the open window.” My mother’s gaze drifts away from my face and travels a great distance.

I was very sick, I remember lying in my bed. Our neighbor was making borscht and the aroma drifted into my room from the open window.” My mother’s gaze drifts away from my face and travels a great distance.

As my mother retells this rare account of her childhood in Nikolayev, I picture her three older brothers off on an adventure with Tusik, their beloved and faithful mutt. Tootka struts and crows outside, wondering who will feed him juicy caterpillars or dragonflies plucked from the wash line. And my mother’s cat Asta is curled up at her feet, snuggled deep in the featherbed.

I return from my reverie as my mother continues, “I told my mother I knew I would get better if only I could have a bowl of that borscht. So, my mother went to our neighbor and came home with some soup for me.”

My mother pauses in her story to enjoy a few spoonfuls of our homemade soup while it’s still nice and hot.

“And, you know what?” my mother concludes, her face beaming. “I was right. As soon as I ate that borscht I was better.”

Listen to Annette read My Mother’s Red Borscht:

Copyright © 2022 by Annette Matjucha Hovland

Annette Matjucha Hovland

Stories Shared Across the Kitchen Table

Annette Matjucha Hovland is an artist of many mediums. A poet, a journalist, a photographer and a teacher, she observes the small and beautiful things in the world and shares them in words and images. She enjoys cooking, especially family recipes that bring back childhood memories and forge a deeper connection to her family’s history and culture.

A native of New Jersey, she currently lives in Muscatine, Iowa. Several of her poems are winners of the annual Wandering Words Poetry Contest and are etched into Muscatine sidewalks, others are published in the Iowa Poetry Association’s anthology, Lyrical Iowa.